Planning October 2019

Justice for All?

Planners are uniquely suited to help disadvantaged communities combat negative environmental effects — and stop them from happening in the future.

Gabriela Wasserman, 11, lived in Chicago's Little Village neighborhood — whose air quality is among the worst in Illinois — for her first nine years. She uses an inhaler to treat her asthma, a condition shared by her two older brothers. Photo by Youngrae Kim.

By Adina Solomon

Chicago was once known for its meat packing, railyards, steel plants, and other industry. While many of those historic uses are long gone, neighborhoods like Little Village, a largely Latinx neighborhood on the Southwest Side, feel the effects even today. Almost half of the community's land is dedicated to industrial uses like large warehouses, asphalt plants, and oil facilities. As a result, Little Village's air quality is among the worst in Illinois.

Local environmental justice advocates had hoped the 2012 closure of a coal plant linked to years of asthma attacks, emergency room visits, and premature deaths was a sign of change. But the victory was short-lived. Today, the plant is being torn down and replaced by a one-million-square-foot distribution warehouse that will generate significant daily diesel semi-truck traffic. The warehouse has sparked anger among residents and concerns of increased air pollution.

Little Village is just one example of a trend that has played out over and over in cities big and small. The legacy of land-use planning placed the least desirable, most environmentally concerning uses — industry, landfills, sewage treatment plants — in the backyards of people of color, leaving them to bear the brunt of environmental effects. And while progress has been made over the years in the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of people "regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to development, implementations, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies" — as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency defines environmental justice — there remains a lot to be done in modern land-use planning and development decisions.

"[These decisions are] too often about economic development," says José Acosta-Córdova, environmental planning and research organizer at Little Village Environmental Justice Organization. "We make decisions based on the number of jobs that are coming or the economic impact of the development versus ... thinking about the impacts it's going to have on the local environment, on the people that live there, and also on the actual natural environment."

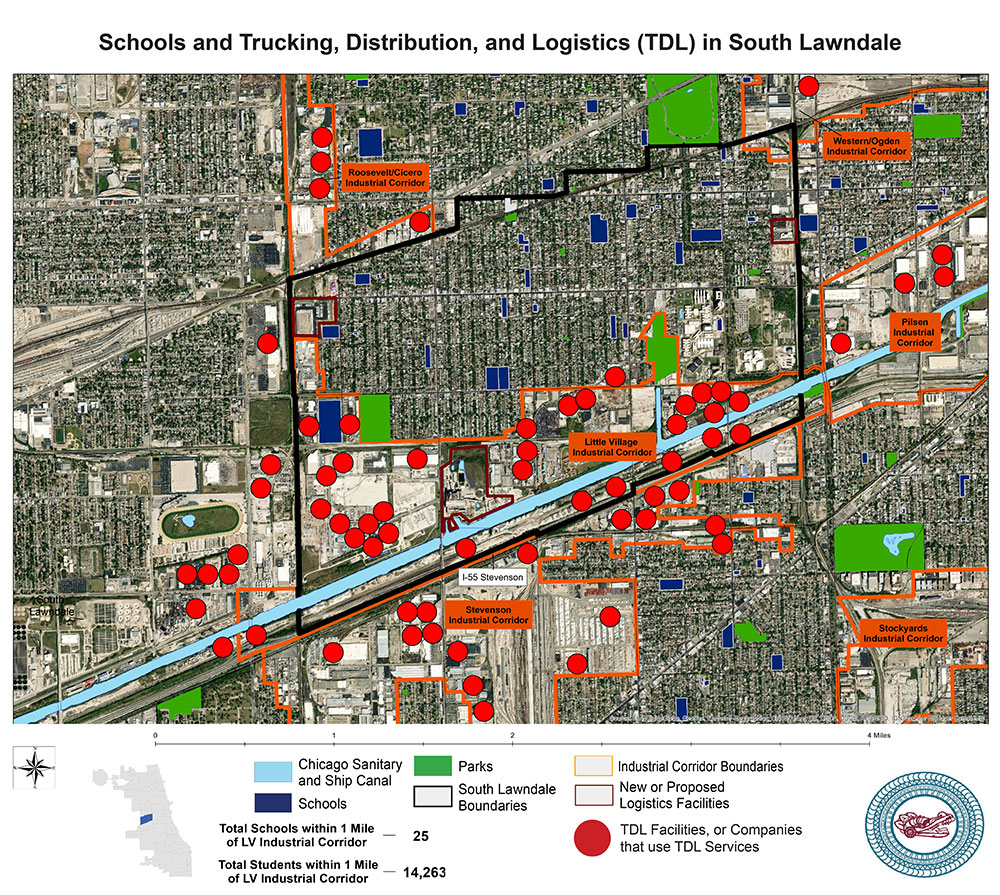

This map of South Lawndale, Chicago, shows the proximity of schools and the more than 30 companies in the Little Village neighborhood that are classified as part of the trucking, distribution, and logistics industry. The three most recent industrial developments, outlined in maroon, are (clockwise from upper left) the Unilever mayonnaise plant (expanded 2017); the Rockwell Logistics Center (constructed 2018); the Hilco Warehouse (under construction), replacing the shuttered Crawford Coal Plant. Source: Little Village Environmental Justice Organization.

Some say it's now up to planners to use the tools at their disposal to help correct what went wrong.

"There's a lot of racism that was embedded in our land-use decisions," says Ana Baptista, chair of the New School's Environmental Policy and Sustainability Management program. "None of it is a happenstance coincidence. It really is a byproduct of housing segregation, redlining, racialized zoning, exploitation in the banking and real estate systems."

Baptista, also an assistant professor of professional practice, says local environmental justice organizations have recently begun harnessing the power of community planning to address the problem. She prepared a 2019 report on EJ land-use policies in more than 20 cities from Atlanta to Minneapolis to Cincinnati.

"A lot of [the policies were] being driven by community-led efforts and community demands from environmental justice groups who didn't just want to tweak zoning," Baptista says. "They wanted a really forward-looking vision and they wanted more comprehensive approaches to some of the issues that they were facing."

That's where planning comes in. While planners once ignored, or in some cases even hindered, environmental justice efforts in low-income communities, especially those of color, they are well equipped and positioned to work with over-burdened communities to find solutions and further equity. With extensive knowledge of land uses and zoning, an understanding of the connection between the environment and planning, and the ability to amend land-use regulations, craft new ones, and guide development, planners are uniquely suited to help these disadvantaged communities combat negative environmental effects — and make sure those injustices don't happen in the future.

"[Planners] see the bigger picture a lot of times, or at least we like to think we do," says Acosta-Córdova. "It's up to us to start leading those conversations."

A family walks next to a railroad track near the Crawford Generating Station in Little Village in Chicago. A contributor to neighborhood respiratory illnesses until it was forced to close in 2012, the 95-year-old building is now being demolished and the site remediated to make way for a million-square-foot distribution center — something residents fear will be another harmful polluter. Photo by Youngrae Kim.

Individualized neighborhood zoning

For three decades, social justice organization Liberty Hill Foundation funded community groups throughout Los Angeles to fight hazardous waste facilities, oil refineries, and highway expansions.

"Low-income communities of color were bearing a disproportionate burden of exposure to toxic chemicals coming from industry, from goods movement corridors, from freeways — just a whole toxic soup of exposure," says Michele Prichard, director of environmental health and justice for the organization.

"We're fighting one little effort at a time," Prichard recalls. Then, in the mid-2000s, Liberty Hill realized this whack-a-mole problem needed an overarching strategy.

"What is really evident here is a systemic land-use problem, where we have conflicting land use, we have sensitive populations of children and families and people who don't have access to health care, people who maybe don't have access to healthy food who are also being just day by day exposed to these hazardous chemicals," she says.

Liberty Hill began by measuring the problem, releasing a 2011 report on air pollution hazards and exposure in the neighborhoods of Wilmington, Boyle Heights, and Pacoima. The report, which relied on community-based participatory research, found that air quality hazards were more numerous than regulatory data suggested. For example, in Boyle Heights, they found an additional 16 hazardous sites not included in the regulatory record.

Liberty Hill spent the next few years figuring out which entities wanted to be involved in cleaning up these neighborhoods and gathering scientific data to back up the community concerns outlined in the report. Their mission: change the zoning codes in these neighborhoods with resident input. In 2013, that goal came closer to reality when Los Angeles's city council authorized the planning department to start work on what became known as the Clean Up Green Up initiative.

The 2016 pilot program entailed two zoning ordinances. The first amended the green building code, while the second created an overlay zone. This zone addressed the top polluting sources in each of the three neighborhoods addressed by Clean Up Green Up, tailoring solutions for each place, says Hagu Solomon-Cary, AICP, a city planner for Los Angeles and lead planner for Clean Up Green Up.

Several highways circumvent Boyle Heights, creating high amounts of car pollution. So the ordinance limited new auto-related businesses within a certain number of feet from residential uses. In Wilmington, oil refineries were a by-right use. The ordinance made them into a conditional use that provided the opportunity for constituents to attend a hearing for new or expanded refineries. Finally, Pacoima has lots of solid waste facilities, so the city decided to widen the notification radius.

"The impacts a solid waste facility can have with leaching can be far more far-reaching than what our current notification requirements were," Solomon-Cary says. "Our thought was we should have more people participating in the public hearing process for those uses."

However, she says, for everything planning can accomplish, it's also important to be honest with stakeholders about what it can't. For example, when the city was establishing what the Clean Up Green Up program would cover, a Liberty Hill consultant submitted 100 requests for regulation changes, some of which were outside the planning department's purview.

"There's only so much the planning and zoning can do on this issue because [environmental justice] is so broad," Solomon-Cary says. "Part of my job was really to manage [the community's and council members'] expectations and ... focus on what land use can do."

In the first two years the ordinances were in effect, 400 new permits were issued for new or expanded building — all required to meet Clean Up Green Up standards, Prichard says. The program's reach is expanding. As Los Angeles currently goes through a rewrite of its zoning codes, it plans on taking principles from the three pilot neighborhoods and adopting some of them throughout the city, Solomon-Cary says.

"They're just what we should have been doing this whole time, protecting adjacent and incompatible uses from one another in a meaningful way," she says. "It was just an important effort to highlight the issue and get people to start thinking about how impactful [it has been to have] decades of industry and residential parks, senior facilities, day cares all packed in with all these different types of pollutants."

Los Angeles County and Minneapolis have also worked on similar measures, and a few Midwestern cities have reached out to Los Angeles for more information.

Not far beyond the white picket fence surrounding a home in the Wilmington neighborhood of Los Angeles is one of three area oil refineries — part of a "systemic land-use problem" that exposes residents to hazardous chemicals. Wilmington is working with the Clean Up Green Up program, which focuses on greening polluted neighborhoods. Photo by Monica Almeida/The New York Times.

Community advocacy

In the mid-1980s, a few years before she cofounded WE ACT for Environmental Justice, Vernice Miller-Travis had a realization. She was working on a 1987 report about toxic waste and race as a researcher at United Church of Christ's Commission for Racial Justice in New York City. She looked at communities across the U.S. and saw the impacts of land-use planning in communities of color, including her own neighborhood of West Harlem in New York City.

It certainly explained the sewage treatment plant. Though it was originally slated for the whiter Upper West Side, it had instead come to West Harlem. The plant had no odor control systems, and the neighborhood experienced poor air quality, year-round mosquitoes, a nightly fog, and a rodent infestation, Miller-Travis says. A trash transfer station and bus depot stood near the sewage plant.

"It was clear that there was a crisis going on in our community and [it] turned out that the answer, the foundation of the crisis, was how land use and zoning were being manipulated based on race," she says.

In 1992, WE ACT for Environmental Justice sued New York City over the air quality caused by the sewage plant. WE ACT settled the lawsuit in 1994, and air quality controls were installed.

Today, WE ACT continues to serve northern Manhattan. Miller-Travis has since entered the planning field and now works as senior advisor for environmental justice and equitable development at Skeo Solutions.

"I just felt like the thing that was trampling the interests of so many communities wherever I went around the country was a lack of ability to inform and shape the local land-use planning process," she says of her career shift. "Sometimes you have a conflict between public health and infrastructure and community impact. And as planners, I think we are called upon to try and figure out a just resolution for that."

That's what she and Skeo did in Freeport, a cornfield-surrounded town in northern Illinois. Miller-Travis came to the town in 2013 to work with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency on the redevelopment of brownfields, but after a community meeting she found that residents' biggest concern was the longtime, routine flooding that kept impacting the same black community that lived near the river.

So Skeo switched its focus to flood mitigation. But the first step, Miller-Travis says, was to tackle the local legacy of racial discrimination. Early in the process, a Skeo colleague conducted training with city government and community representatives on building cultural competence. "The racial tension was so thick in this place, so thick, that you weren't going to be able to have any productive conversations until you did something to open up the space about the legacy of racial discrimination in this community," she says. "And of course, the legacy is thrown in people's faces every freaking time it rains."

Next, to further advance the conversation, Skeo created a GIS map based on where the community members said flooding happened. The map eventually helped them discover that most of the flooding was being caused by a failed stormwater system in desperate need of updating; some of the sewers were made of clay and dated from the 19th century, Miller-Travis says.

Freeport ended up appropriating $350,000 to start repairing the stormwater system. Skeo wrote a 2016 report to give the city and community other resources to pursue for repairs, including federal and state grant programs. Freeport eventually got an EPA grant to build a plan for a waterfront revitalization for the entire town, not just one neighborhood.

"Once we helped to take away the tension and the distrust, they were able to really come to the table and then really think long-term about what they wanted to see happen in their city," Miller-Travis says.

WE ACT, the group Miller-Travis cofounded years ago, has also examined flooding in minority neighborhoods as an environmental justice issue. One of WE ACT's most recent projects involved New York City Housing Authority's Dyckman Houses, home to 2,319 low-income residents, 98 percent of whom are people of color.

NYCHA is rezoning the Inwood neighborhood, which includes putting another building on the already flood-prone Dyckman property. Residents felt that the city wasn't doing the necessary community engagement and that the rezoning needed further study, so WE ACT pulled in a planner to help them develop a set of recommendations for outdoor and indoor environments to improve residents' health and well-being, including addressing flooding.

6 Zoning and Land-Use Strategies to Advance Environmental Justice

Learn from these cities' practical models how local policies can proactively tackle issues of environmental injustice. Read Ana Baptista's full 2019 report, Local Policies for Environmental Justice: A National Scan, at on.nrdc.org/2Lahjxl.

1. BANS ON LAND USES or types of facilities deemed harmful to public health and the environment.

Existing policies: Baltimore; Chicago; Oakland, California; Portland, Oregon; Seattle and Whatcom County, Washington

2. ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE POLICIES AND PROGRAMS that incorporate EJ goals and considerations into a range of municipal activities, particularly land-use policies.

Existing policies: Fulton County, Georgia; New York City; San Francisco

3. ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW PROCESSES for development to ensure proposed projects do not exacerbate impacts in overburdened communities.

Existing policies: Fulton County, Georgia; Camden City, New Jersey; San Francisco; Cincinnati; Newark, New Jersey; New Jersey EJ Alliance; Boston University

4. PROACTIVE PLANNING that guides future growth to address environmental justice via comprehensive plans, overlay zones, and green zones.

Existing policies: Fulton County, Georgia; National City, California; San Francisco; Minneapolis; Washington, D.C.; Los Angeles; Los Angeles County; Seattle Public Utility; Austin, Texas; Eugene, Oregon; Commerce, California

5. TARGETED LAND-USE MEASURES that address existing land uses that disproportionately impact communities, including buffer zones, amortization policies, and code enforcement.

Existing policies: Huntington Park, California; National City, California; San Francisco; Minneapolis; Washington, D.C.

6. ENHANCED PUBLIC HEALTH CODES that protect residents from nuisances that cause or aggravate health issues.

Existing policies: Denver; Chicago; San Francisco; Erie, Colorado; Richmond, California; Detroit

Source: Local Policies for Environmental Justice: A National Scan

Farzana Gandhi, principal for architecture and planning practice at Farzana Gandhi Design Studio, led several community-based workshops, not only to better understand residents' needs and concerns, but also to educate them in principles of urban planning and local land-use laws.

"Planners and architects are really quite critical in the process because we can work on two levels," Gandhi says. "We can work at the community level and really start to impart a level of education to the community. Often, they don't know what they can fight for, and so part of it is training and education and awareness. We also then have the expertise to develop reports and work with elected officials on a much more advocacy level where we can have discussions in a knowledgeable way for these communities."

Génesis Abreu, former bilingual community organizer and outreach coordinator for WE ACT, agrees. "Having the planner there really guiding us helped us communicate a lot of what was happening politically in the community and allowed us to ensure that the folks from Dyckman Houses really had a say," she says.

Since the city established an overlay district to curb industrial uses, the East Austin, Texas, neighborhood has better air quality and less noise pollution. Now the area's improved livability and higher property values mean gentrification is on the rise. Photo by John Davidson.

Considering gentrification

But the quest for justice for these environmentally burdened communities doesn't end once an area is cleaned up. According to environmental justice advocates, it is also crucial to consider potential new burdens on longtime residents as their neighborhoods become healthier, more desirable places to live: rising living costs and, if action isn't taken, displacement.

Austin, Texas knows this well. The city has had to contend with displacement of low-income, minority residents after cleaning up its eastern side in the 1990s. The problem began in 1928, when Austin's master plan segregated the city by moving community services for black and Latinx residents to East Austin. Residents who tried to live elsewhere were often denied access to services.

East Austin was also home to industry and truck traffic. This created pollution, noise, and air quality issues, says Greg Guernsey, AICP, former director of Austin's Planning and Zoning Department. Petroleum products had leached from tanks, contaminating the soil, and federal and state laws only required a minimum level of cleanup since the area was industrial, not residential.

"So you could still use it for commercial, but you couldn't use it for living," Guernsey says.

A tank farm that not only created truck traffic but also leached oil into the ground, causing a resident uproar, led the city to address pollution in East Austin in the 1990s by creating a moratorium on certain industrial and commercial uses such as petrochemical plants and tank farms. Out of this work came the East Austin overlay, a temporary tool that made industrial, manufacturing, and warehousing uses conditional.

"It was pretty controversial because we just took all these uses that were conforming and basically made them all nonconforming," says Guernsey, who was manager of the zoning section for the overlay district.

Austin's city council chose an overlay district because it was a quick way to begin solving the problem. And it worked. By the early 2000s, the vast majority of properties went from industrial to a commercial mixed-use district that allowed housing, and the city sunsetted the overlay district. Austin then created neighborhood plans to continue to address pollution by downzoning and removing the ability to have industrial uses in these areas.

Today, East Austin has improved air quality and reduced noise pollution because of the lower truck traffic and industrial operations, Guernsey says.

However, in the years since the cleanup, longtime residents have faced a different kind of burden: East Austin has become more gentrified. "Land values now are just rocketing," Guernsey says. "People just can't afford to live there because they're low-income or they're on fixed income."

Austin has taken strides to maintain affordability for residents, including approving a housing blueprint that highlights funding mechanisms, potential regulations, and other approaches the city can use to achieve affordable housing goals. The city also passed a $250 million affordable housing bond and created an equity office in 2016 to train all departments on these issues.

Environmental and equity issues are bound together, Guernsey says, and these problems exist in many cities' histories. He says it's up to planners to make sure everyone has a healthy place to live, including everything from air and water quality to odors, he says.

"Everyone should have a place that they feel safe, not only from a crime and health standpoint but just for mental ability, to have a place they can feel like it's home and it's inviting," Guernsey says.

"Environmental justice is more than maybe just cleaning up that mess over there that somebody spilled or rerouting a truck here and there. It's that whole package."

Adina Solomon is a freelance journalist based in Atlanta. Among other topics, she writes about city planning and design. Her bylines have appeared in the Washington Post, CityLab, and Next City.

Resources

Resilience for All: Barbara Brown Wilson explores patterns of injustice in eight communities that are driving positive change.

In JAPA: "Racial and Class Bias in Zoning": Andrew Whittemore examines 60 years of commercial and industrial rezonings in Durham, North Carolina.